Delayering Istio with AppSwitch

The sidecar proxy approach enables a lot of awesomeness. Squarely in the datapath between microservices, the sidecar can precisely tell what the application is trying to do. It can monitor and instrument protocol traffic, not in the bowels of the networking layers but at the application level, to enable deep visibility, access controls and traffic management.

If we look closely however, there are many intermediate layers that the data has to pass through before the high-value analysis of application-traffic can be performed. Most of those layers are part of the base plumbing infrastructure that are there just to push the data along. In doing so, they add latency to communication and complexity to the overall system.

Over the years, there has been much collective effort in implementing aggressive fine-grained optimizations within the layers of the network datapath. Each iteration may shave another few microseconds. But then the true necessity of those layers itself has not been questioned.

Don’t optimize layers, remove them

In my belief, optimizing something is a poor fallback to removing its requirement altogether. That was the goal of my initial work (broken link: https://apporbit.com/a-brief-history-of-containers-from-reality-to-hype/) on OS-level virtualization that led to Linux containers which effectively removed virtual machines by running applications directly on the host operating system without requiring an intermediate guest. For a long time the industry was fighting the wrong battle distracted by optimizing VMs rather than removing the additional layer altogether.

I see the same pattern repeat itself with the connectivity of microservices, and networking in general. The network has been going through the changes that physical servers have gone through a decade earlier. New set of layers and constructs are being introduced. They are being baked deep into the protocol stack and even silicon without adequately considering low-touch alternatives. Perhaps there is a way to remove those additional layers altogether.

I have been thinking about these problems for some time and believe that an approach similar in concept to containers can be applied to the network stack that would fundamentally simplify how application endpoints are connected across the complexity of many intermediate layers. I have reapplied the same principles from the original work on containers to create AppSwitch. Similar to the way containers provide an interface that applications can directly consume, AppSwitch plugs directly into well-defined and ubiquitous network API that applications currently use and directly connects application clients to appropriate servers, skipping all intermediate layers. In the end, that’s what networking is all about.

Before going into the details of how AppSwitch promises to remove unnecessary layers from the Istio stack, let me give a very brief introduction to its architecture. Further details are available at the documentation page.

AppSwitch

Not unlike the container runtime, AppSwitch consists of a client and a daemon that speak over HTTP via a REST API. Both the client and the daemon are built as one self-contained binary, ax. The client transparently plugs into the application and tracks its system calls related to network connectivity and notifies the daemon about their occurrences. As an example, let’s say an application makes the connect(2) system call to the service IP of a Kubernetes service. The AppSwitch client intercepts the connect call, nullifies it and notifies the daemon about its occurrence along with some context that includes the system call arguments. The daemon would then handle the system call, potentially by directly connecting to the Pod IP of the upstream server on behalf of the application.

It is important to note that no data is forwarded between AppSwitch client and daemon. They are designed to exchange file descriptors (FDs) over a Unix domain socket to avoid having to copy data. Note also that client is not a separate process. Rather it directly runs in the context of the application itself. There is no data copy between the application and AppSwitch client either.

Delayering the stack

Now that we have an idea about what AppSwitch does, let’s look at the layers that it optimizes away from a standard service mesh.

Network devirtualization

Kubernetes offers simple and well-defined network constructs to the microservice applications it runs. In order to support them however, it imposes specific requirements on the underlying network. Meeting those requirements is often not easy. The go-to solution of adding another layer is typically adopted to satisfy the requirements. In most cases the additional layer consists of a network overlay that sits between Kubernetes and underlying network. Traffic produced by the applications is encapsulated at the source and decapsulated at the target, which not only costs network resources but also takes up compute cores.

Because AppSwitch arbitrates what the application sees through its touchpoints with the platform, it projects a consistent virtual view of the underlying network to the application similar to an overlay but without introducing an additional layer of processing along the datapath. Just to draw a parallel to containers, the inside of a container looks and feels like a VM. However the underlying implementation does not intervene along the high-incidence control paths of low-level interrupts etc.

AppSwitch can be injected into a standard Kubernetes manifest (similar to Istio injection) such that the application’s network is directly handled by AppSwitch bypassing any network overlay underneath. More details to follow in just a bit.

Artifacts of container networking

Extending network connectivity from host into the container has been a major challenge. New layers of network plumbing were invented explicitly for that purpose. As such, an application running in a container is simply a process on the host. However due to a fundamental misalignment between the network abstraction expected by the application and the abstraction exposed by container network namespace, the process cannot directly access the host network. Applications think of networking in terms of sockets or sessions whereas network namespaces expose a device abstraction. Once placed in a network namespace, the process suddenly loses all connectivity. The notion of veth-pair and corresponding tooling were invented just to close that gap. The data would now have to go from a host interface into a virtual switch and then through a veth-pair to the virtual network interface of the container network namespace.

AppSwitch can effectively remove both the virtual switch and veth-pair layers on both ends of the connection. Since the connections are established by the daemon running on the host using the network that’s already available on the host, there is no need for additional plumbing to bridge host network into the container. The socket FDs created on the host are passed to the application running within the pod’s network namespace. By the time the application receives the FD, all control path work (security checks, connection establishment) is already done and the FD is ready for actual IO.

Skip TCP/IP for colocated endpoints

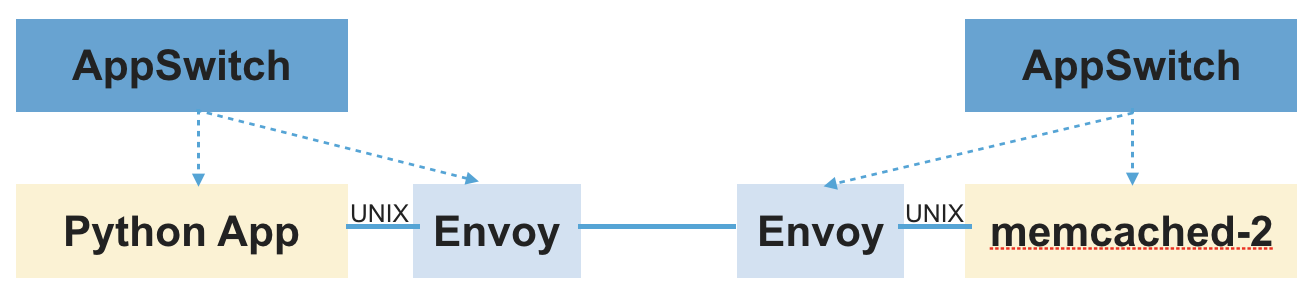

TCP/IP is the universal protocol medium over which pretty much all communication occurs. But if application endpoints happen to be on the same host, is TCP/IP really required? After all, it does do quite a bit of work and it is quite complex. Unix sockets are explicitly designed for intrahost communication and AppSwitch can transparently switch the communication to occur over a Unix socket for colocated endpoints.

For each listening socket of an application, AppSwitch maintains two listening sockets, one each for TCP and Unix. When a client tries to connect to a server that happens to be colocated, AppSwitch daemon would choose to connect to the Unix listening socket of the server. The resulting Unix sockets on each end are passed into respective applications. Once a fully connected FD is returned, the application would simply treat it as a bit pipe. The protocol doesn’t really matter. The application may occasionally make protocol specific calls such as getsockname(2) and AppSwitch would handle them in kind. It would present consistent responses such that the application would continue to run on.

Data pushing proxy

As we continue to look for layers to remove, let us also reconsider the requirement of the proxy layer itself. There are times when the role of the proxy may degenerate into a plain data pusher:

- There may not be a need for any protocol decoding

- The protocol may not be recognized by the proxy

- The communication may be encrypted and the proxy cannot access relevant headers

- The application (redis, memcached etc.) may be too latency-sensitive and cannot afford the cost of an intermediate proxy

In all these cases, the proxy is not different from any low-level plumbing layer. In fact, the latency introduced can be far higher because the same level of optimizations won’t be available to a proxy.

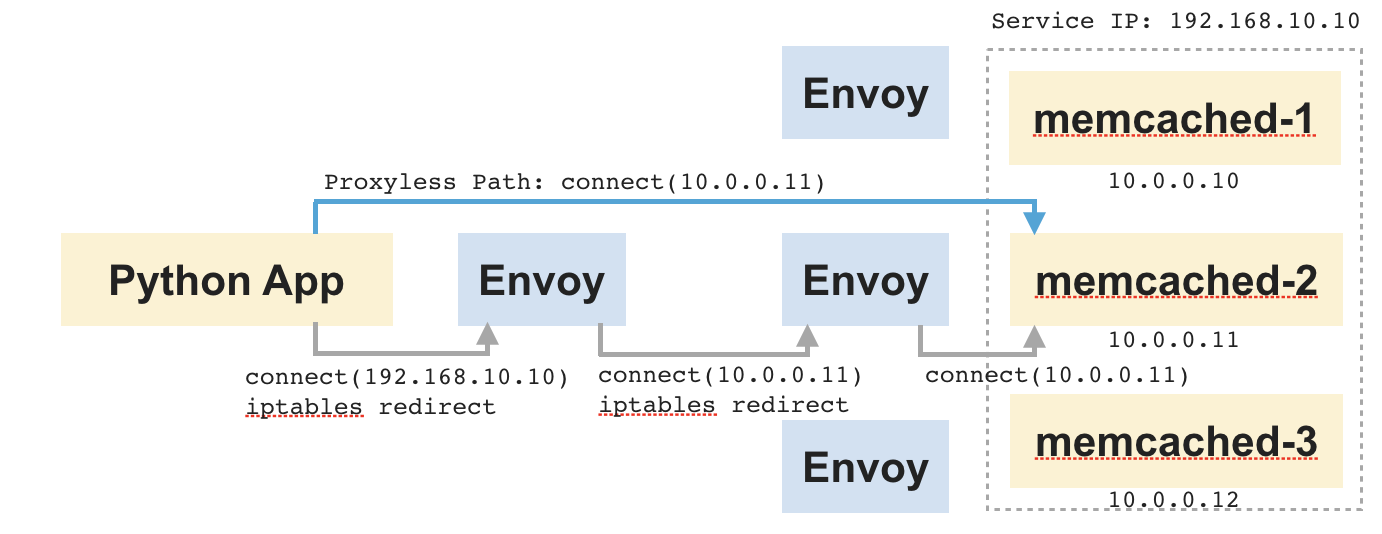

To illustrate this with an example, consider the application shown below. It consists of a Python app and a set of memcached servers behind it. An upstream memcached server is selected based on connection time routing. Speed is the primary concern here.

If we look at the data flow in this setup, the Python app makes a connection to the service IP of memcached. It is redirected to the client-side sidecar. The sidecar routes the connection to one of the memcached servers and copies the data between the two sockets – one connected to the app and another connected to memcached. And the same also occurs on the server side between the server-side sidecar and memcached. The role of proxy at that point is just boring shoveling of bits between the two sockets. However, it ends up adding substantial latency to the end-to-end connection.

Now let us imagine that the app is somehow made to connect directly to memcached, then the two intermediate proxies could be skipped. The data would flow directly between the app and memcached without any intermediate hops. AppSwitch can arrange for that by transparently tweaking the target address passed by the Python app when it makes the connect(2) system call.

Proxyless protocol decoding

Things are going to get a bit strange here. We have seen that the proxy can be bypassed for cases that don’t involve looking into application traffic. But is there anything we can do even for those other cases? It turns out, yes.

In a typical communication between microservices, much of the interesting information is exchanged in the initial headers. Headers are followed by body or payload which typically represents bulk of the communication. And once again the proxy degenerates into a data pusher for this part of communication. AppSwitch provides a nifty mechanism to skip proxy for these cases.

Even though AppSwitch is not a proxy, it does arbitrate connections between application endpoints and it does have access to corresponding socket FDs. Normally, AppSwitch simply passes those FDs to the application. But it can also peek into the initial message received on the connection using the MSG_PEEK option of the recvfrom(2) system call on the socket. It allows AppSwitch to examine application traffic without actually removing it from the socket buffers. When AppSwitch returns the FD to the application and steps out of the datapath, the application would do an actual read on the connection. AppSwitch uses this technique to perform deeper analysis of application-level traffic and implement sophisticated network functions as discussed in the next section, all without getting into the datapath.

Zero-cost load balancer, firewall and network analyzer

Typical implementations of network functions such as load balancers and firewalls require an intermediate layer that needs to tap into data/packet stream. Kubernetes’ implementation of load balancer (kube-proxy) for example introduces a probe into the packet stream through iptables and Istio implements the same at the proxy layer. But if all that is required is to redirect or drop connections based on policy, it is not really necessary to stay in the datapath during the entire course of the connection. AppSwitch can take care of that much more efficiently by simply manipulating the control path at the API level. Given its intimate proximity to the application, AppSwitch also has easy access to various pieces of application level metrics such as dynamics of stack and heap usage, precisely when a service comes alive, attributes of active connections etc., all of which could potentially form a rich signal for monitoring and analytics.

To go a step further, AppSwitch can also perform L7 load balancing and firewall functions based on the protocol data that it obtains from the socket buffers. It can synthesize the protocol data and various other signals with the policy information acquired from Pilot to implement a highly efficient form of routing and access control enforcement. It can essentially “influence” the application to connect to the right backend server without requiring any changes to the application or its configuration. It is as if the application itself is infused with policy and traffic-management intelligence. Except in this case, the application can’t escape the influence.

There is some more black-magic possible that would actually allow modifying the application data stream without getting into the datapath but I am going to save that for a later post. Current implementation of AppSwitch uses a proxy if the use case requires application protocol traffic to be modified. For those cases, AppSwitch provides a highly optimal mechanism to attract traffic to the proxy as discussed in the next section.

Traffic redirection

Before the sidecar proxy can look into application protocol traffic, it needs to first receive the connections. Redirection of connections coming into and going out of the application is currently done by a layer of packet filtering that rewrites packets such that they go to respective sidecars. Creating potentially large number of rules required to represent the redirection policy is tedious. And the process of applying the rules and updating them, as the target subnets to be captured by the sidecar change, is expensive.

While some of the performance concerns are being addressed by the Linux community, there is another concern related to privilege: iptables rules need to be updated whenever the policy changes. Given the current architecture, all privileged operations are performed in an init container that runs just once at the very beginning before privileges are dropped for the actual application. Since updating iptables rules requires root privileges, there is no way to do that without restarting the application.

AppSwitch provides a way to redirect application connections without root privilege. As such, an unprivileged application is already able to connect to any host (modulo firewall rules etc.) and the owner of the application should be allowed to change the host address passed by its application via connect(2) without requiring additional privilege.

Socket delegation

Let’s see how AppSwitch could help redirect connections without using iptables. Imagine that the application somehow voluntarily passes the socket FDs that it uses for its communication to the sidecar, then there would be no need for iptables. AppSwitch provides a feature called socket delegation that does exactly that. It allows the sidecar to transparently gain access to copies of socket FDs that the application uses for its communication without any changes to the application itself.

Here are the sequence of steps that would achieve this in the context of the Python application example.

- The application initiates a connection request to the service IP of memcached service.

- The connection request from client is forwarded to the daemon.

- The daemon creates a pair of pre-connected Unix sockets (using

socketpair(2)system call). - It passes one end of the socket pair into the application such that the application would use that socket FD for read/write. It also ensures that the application consistently sees it as a legitimate TCP socket as it expects by interposing all calls that query connection properties.

- The other end is passed to sidecar over a different Unix socket where the daemon exposes its API. Information such as the original destination that the application was connecting to is also conveyed over the same interface.

Once the application and sidecar are connected, the rest happens as usual. Sidecar would initiate a connection to upstream server and proxy data between the socket received from the daemon and the socket connected to upstream server. The main difference here is that sidecar would get the connection, not through the accept(2) system call as it is in the normal case, but from the daemon over the Unix socket. In addition to listening for connections from applications through the normal accept(2) channel, the sidecar proxy would connect to the AppSwitch daemon’s REST endpoint and receive sockets that way.

For completeness, here are the sequence of steps that would occur on the server side:

- The application receives a connection

- AppSwitch daemon accepts the connection on behalf of the application

- It creates a pair of pre-connected Unix sockets using

socketpair(2)system call - One end of the socket pair is returned to the application through the

accept(2)system call - The other end of the socket pair along with the socket originally accepted by the daemon on behalf of the application is sent to sidecar

- Sidecar would extract the two socket FDs – a Unix socket FD connected to the application and a TCP socket FD connected to the remote client

- Sidecar would read the metadata supplied by the daemon about the remote client and perform its usual operations

“Sidecar-aware” applications

Socket delegation feature can be very useful for applications that are explicitly aware of the sidecar and wish to take advantage of its features. They can voluntarily delegate their network interactions by passing their sockets to the sidecar using the same feature. In a way, AppSwitch transparently turns every application into a sidecar-aware application.

How does it all come together?

Just to step back, Istio offloads common connectivity concerns from applications to a sidecar proxy that performs those functions on behalf of the application. And AppSwitch simplifies and optimizes the service mesh by sidestepping intermediate layers and invoking the proxy only for cases where it is truly necessary.

In the rest of this section, I outline how AppSwitch may be integrated with Istio based on a very cursory initial implementation. This is not intended to be anything like a design doc – not every possible way of integration is explored and not every detail is worked out. The intent is to discuss high-level aspects of the implementation to present a rough idea of how the two systems may come together. The key is that AppSwitch would act as a cushion between Istio and a real proxy. It would serve as the “fast-path” for cases that can be performed more efficiently without invoking the sidecar proxy. And for the cases where the proxy is used, it would shorten the datapath by cutting through unnecessary layers. Look at this blog for a more detailed walk through of the integration.

AppSwitch client injection

Similar to Istio sidecar-injector, a simple tool called ax-injector injects AppSwitch client into a standard Kubernetes manifest. Injected client transparently monitors the application and intimates AppSwitch daemon of the control path network API events that the application produces.

It is possible to not require the injection and work with standard Kubernetes manifests if AppSwitch CNI plugin is used. In that case, the CNI plugin would perform necessary injection when it gets the initialization callback. Using injector does have some advantages, however: (1) It works in tightly-controlled environments like GKE (2) It can be easily extended to support other frameworks such as Mesos (3) Same cluster would be able to run standard applications alongside “AppSwitch-enabled” applications.

AppSwitch DaemonSet

AppSwitch daemon can be configured to run as a DaemonSet or as an extension to the application that is directly injected into application manifest. In either case it handles network events coming in from the applications that it supports.

Agent for policy acquisition

This is the component that conveys policy and configuration dictated by Istio to AppSwitch. It implements xDS API to listen from Pilot and calls appropriate AppSwitch APIs to program the daemon. For example, it allows the load balancing strategy, as specified by istioctl, to be translated into equivalent AppSwitch capability.

Platform adapter for AppSwitch “Auto-Curated” service registry

Given that AppSwitch is in the control path of applications’ network APIs, it has ready access to the topology of services across the cluster. AppSwitch exposes that information in the form of a service registry that is automatically and (almost) synchronously updated as applications and their services come and go. A new platform adapter for AppSwitch alongside Kubernetes, Eureka etc. would provide the details of upstream services to Istio. This is not strictly necessary but it does make it easier to correlate service endpoints received from Pilot by AppSwitch agent above.

Proxy integration and chaining

Connections that do require deep scanning and mutation of application traffic are handed off to an external proxy through the socket delegation mechanism discussed earlier. It uses an extended version of proxy protocol. In addition to the simple parameters supported by the proxy protocol, a variety of other metadata (including the initial protocol headers obtained from the socket buffers) and live socket FDs (representing application connections) are forwarded to the proxy.

The proxy can look at the metadata and decide how to proceed. It could respond by accepting the connection to do the proxying or by directing AppSwitch to allow the connection and use the fast-path or to just drop the connection.

One of the interesting aspects of the mechanism is that, when the proxy accepts a socket from AppSwitch, it can in turn delegate the socket to another proxy. In fact that is how AppSwitch currently works. It uses a simple built-in proxy to examine the metadata and decide whether to handle the connection internally or to hand it off to an external proxy (Envoy). The same mechanism can be potentially extended to allow for a chain of plugins, each looking for a specific signature, with the last one in the chain doing the real proxy work.

It’s not just about performance

Removing intermediate layers along the datapath is not just about improving performance. Performance is a great side effect, but it is a side effect. There are a number of important advantages to an API level approach.

Automatic application onboarding and policy authoring

Before microservices and service mesh, traffic management was done by load balancers and access controls were enforced by firewalls. Applications were identified by IP addresses and DNS names which were relatively static. In fact, that’s still the status quo in most environments. Such environments stand to benefit immensely from service mesh. However a practical and scalable bridge to the new world needs to be provided. The difficulty in transformation is not as much due to lack of features and functionality but the investment required to rethink and reimplement the entire application infrastructure. Currently most of the policy and configuration exists in the form of load balancer and firewall rules. Somehow that existing context needs to be leveraged in providing a scalable path to adopting the service mesh model.

AppSwitch can substantially ease the onboarding process. It can project the same network environment to the application at the target as its current source environment. Not having any assistance here is typically a non-starter in case of traditional applications which have complex configuration files with static IP addresses or specific DNS names hard-coded in them. AppSwitch could help capture those applications along with their existing configuration and connect them over a service mesh without requiring any changes.

Broader application and protocol support

HTTP clearly dominates the modern application landscapes but once we talk about traditional applications and environments, we’d encounter all kinds of protocols and transports. Particularly, support for UDP becomes unavoidable. Traditional application servers such as IBM WebSphere rely extensively on UDP. Most multimedia applications use UDP media streams. Of course DNS is probably the most widely used UDP “application”. AppSwitch supports UDP at the API level much the same way as TCP and when it detects a UDP connection, it can transparently handle it in its “fast-path” rather than delegating it to the proxy.

Client IP preservation and end-to-end principle

The same mechanism that preserves the source network environment can also preserve client IP addresses as seen by the servers. With a sidecar proxy in place, connection requests come from the proxy rather than the client. As a result, the peer address (IP:port) of the connection as seen by the server would be that of the proxy rather than the client. AppSwitch ensures that the server sees correct address of the client, logs it correctly and any decisions made based on the client address remain valid. More generally, AppSwitch preserves the end-to-end principle which is otherwise broken by intermediate layers that obfuscate the true underlying context.

Enhanced application signal with access to encrypted headers

Encrypted traffic completely undermines the ability of the service mesh to analyze application traffic. API level interposition could potentially offer a way around it. Current implementation of AppSwitch gains access to application’s network API at the system call level. However it is possible in principle to influence the application at an API boundary, higher in the stack where application data is not yet encrypted or already decrypted. Ultimately the data is always produced in the clear by the application and then encrypted at some point before it goes out. Since AppSwitch directly runs within the memory context of the application, it is possible to tap into the data higher on the stack where it is still held in clear. Only requirement for this to work is that the API used for encryption should be well-defined and amenable for interposition. Particularly, it requires access to the symbol table of the application binaries. Just to be clear, AppSwitch doesn’t implement this today.

So what’s the net?

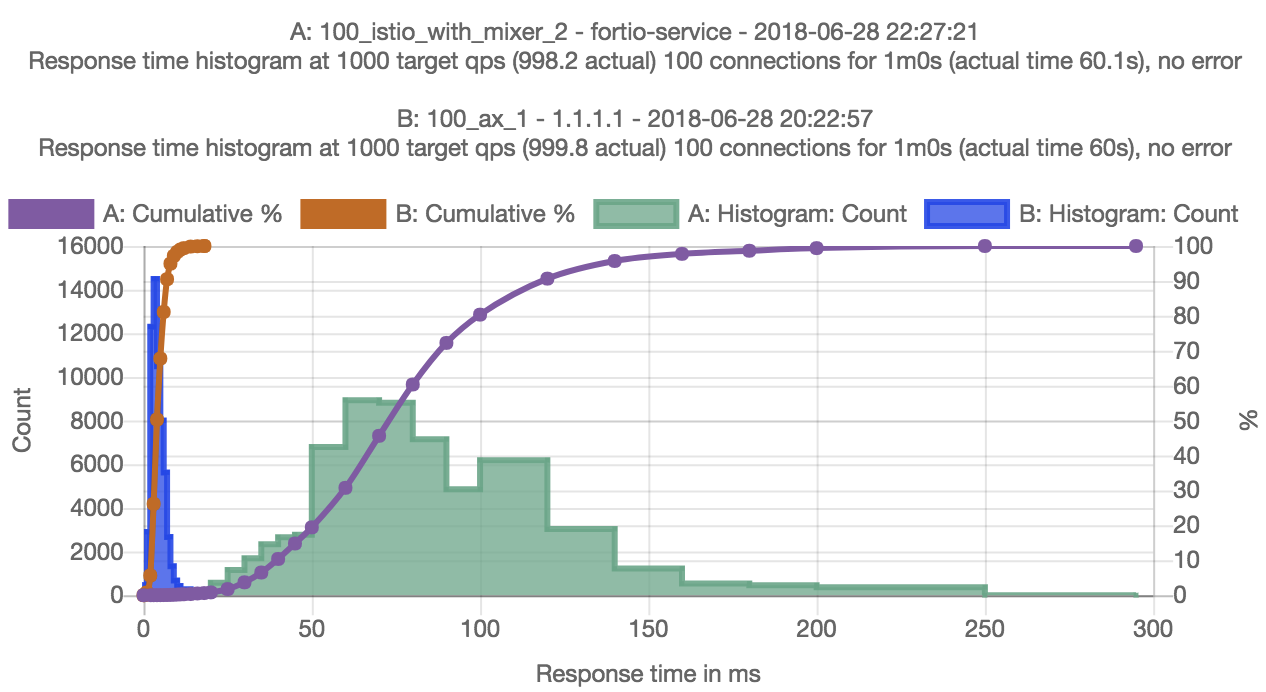

AppSwitch removes a number of layers and processing from the standard service mesh stack. What does all that translate to in terms of performance?

We ran some initial experiments to characterize the extent of the opportunity for optimization based on the initial integration of AppSwitch discussed earlier. The experiments were run on GKE using fortio-0.11.0, istio-0.8.0 and appswitch-0.4.0-2. In case of the proxyless test, AppSwitch daemon was run as a DaemonSet on the Kubernetes cluster and the Fortio pod spec was modified to inject AppSwitch client. These were the only two changes made to the setup. The test was configured to measure the latency of GRPC requests across 100 concurrent connections.

Initial results indicate a difference of over 18x in p50 latency with and without AppSwitch (3.99ms vs 72.96ms). The difference was around 8x when mixer and access logs were disabled. Clearly the difference was due to sidestepping all those intermediate layers along the datapath. Unix socket optimization wasn’t triggered in case of AppSwitch because client and server pods were scheduled to separate hosts. End-to-end latency of AppSwitch case would have been even lower if the client and server happened to be colocated. Essentially the client and server running in their respective pods of the Kubernetes cluster are directly connected over a TCP socket going over the GKE network – no tunneling, bridge or proxies.

Net Net

I started out with David Wheeler’s seemingly reasonable quote that says adding another layer is not a solution for the problem of too many layers. And I argued through most of the blog that current network stack already has too many layers and that they should be removed. But isn’t AppSwitch itself a layer?

Yes, AppSwitch is clearly another layer. However it is one that can remove multiple other layers. In doing so, it seamlessly glues the new service mesh layer with existing layers of traditional network environments. It offsets the cost of sidecar proxy and as Istio graduates to 1.0, it provides a bridge for existing applications and their network environments to transition to the new world of service mesh.

Perhaps Wheeler’s quote should read:

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mandar Jog (Google) for several discussions about the value of AppSwitch for Istio and to the following individuals (in alphabetical order) for their review of early drafts of this blog.

- Frank Budinsky (IBM)

- Lin Sun (IBM)

- Shriram Rajagopalan (VMware)